Introduction

The constant reengineering of many organizations appears to have diminished the number of middle managers in these organizations dramatically (Clarke 1998; Dopson & Stewart 1983; Floyd and Wooldridge 1994; Hayes, 2008). At the same time, Huy (2002) argued that middle managers play an important role in facilitating change in organizations. They may have value-adding ideas for making the organization better, tend to have a big informal network within the organization, and can help the organization to strike a balance between continuity and change.

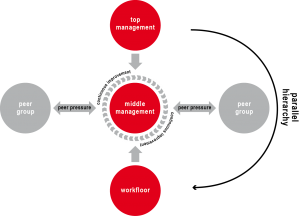

Figure: Playing field of middle management

Without pretending to be complete the above figure shows the demanding playing field of middle management which we will look into in some more detail.

Middle management and continuous improvement

Implementing any Continuous Improvement (CI) method appears to demand big changes in the organization and mindset of the people involved (Drew et al. 2004). One key reason for the failure of CI methods has been said to be poor leadership (Lucey et al. 2005), and particularly the role of middle managers in facilitating sustaining change (Fine et al. 2008). Middle management can have a big role in this, through their creative and innovative skills, informal network and knowledge about what motivates employees (Huy 2001; Moss Kanter 1982). Although continuous improvement programs are often initiated by referring to ‘sustained improvement’ and similar terms, they often end up as a quick fix of problems without a deliberate effort to create and maintain the conditions needed (Bhuiyan, Baghel & Wilson 2006; Snee 2010). However, the function and position of middle managers is also a very difficult one, between operational and upper management and between operations and strategy.

Middle management and parallel hierarchy

Another important theme, is empowerment. Empowerment of employees may cause anxiety among middle managers when they can no longer control decisions made at lower levels and formal communication channels are changed. In this respect, by empowering people middle managers have to enable employees to take responsibility for their own actions and success and give up some control. As such, middle managers (are expected to) move away from the role of supervisor to the role of coach. As a result, they experience insecurity, which is reinforced by what is perceived to be a parallel hierarchy (Denham et al. 1997; Fenton-O’Creevy 2001; Psychogios, Wilkinson & Szamosi 2009; Holden & Roberts 2004).

Middle management and top management

For the sustainability of a CI practice, the commitment, involvement and leadership of the entire management of the organization are critical (Snee 2010; Dahlgaard & Dahlgaard-Park 2006). As culture and values are to a large extent top management driven, the role of top management in the implementation of CI is critical here. Top management needs to actively support and lead by example when dealing with empowerment. In addition, top management is responsible for creating a change-oriented culture and adopting new organization-wide ways of working. Hence, top management should stimulate a cultural change to support the CI principles throughout the organization (Mann 2009; Snee 2010).

Middle management and the work floor

Middle managers thus find themselves in a struggle to survive (Spreitzer & Quinn 1996), particularly when they perceive the empowering of their subordinates as beneficial to the organization but not beneficial to themselves (Denham et al. 1997). Middle managers have also been observed to actively block empowerment in order to preserve the power and status they felt were being reduced or lost (Denham et al 1997). In this context potential resistance of middle management to employee involvement can be observed (Fenton-O’Creevy 2001).

Middle management and peer pressure

Moreover, the workforce may demoralize because of the pressure from downsizing and potentially losing one’s job, which may result in stressed managers and lower productivity (Harrington & Williams 2004). Downsizing has also led to reduced job security for middle managers and increased work pressure and peer pressure, because the remaining middle managers need to work harder and longer and have a higher span of control (McCann et al. 2008; Robyn & Dunkerley 1999; Keys & Bell 1982).

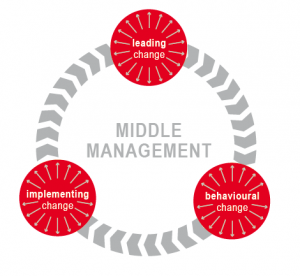

Capstone

Continuous improvement (CI) can be seen as a state in an organization in which all members of the organization contribute to performance improvement by continuously implementing small changes in their work processes (Jørgensen et al. 2003). Where the initial focus was on cutting cost, CI methods have evolved towards a focus on changing the organizational culture (Bhasin & Burcher 2006). Some studies of the lean approach demonstrate that it requires a change in mindset and behavior among its leaders (Mann 2009). O’Rourke (2005) notes three important issues regarding leadership: the leadership’s responsibility to influence business strategy with CI, the leadership’s direct involvement in the deployment design process, and leadership’s active engagement in the implementation. Leadership is an important element when creating the urgency of change that is necessary for creating continuous improvement within an organization. Middle managers need to take a leading role. This is not an easy job because they have to change their own mindset and behavior and lead by example. Commitment and a change in behavior and attitude from the entire organization, middle management included, is a critical factor for achieving sustainability.

References

Bhasin, S. & Burcher, P. 2006, “Lean viewed as a philosophy“, Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, vol. 17, no. 1/2, pp. 56-72.

Bhuiyan, N., Baghel, A. & Wilson, J. 2006 “A sustainable continuous improvement methodology at an aerospace company”, International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, vol. 55, no. 8, pp. 671-687.

Clarke, M. 1998, “Can specialists be general managers? Developing paradoxical thinking in middle managers” The Journal of Management Development, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 191-206.

Dahlgaard, J. & Dahlgaard-Park, S. 2006, “Lean production, six sigma quality, TQM and company culture”, The TQM Magazine, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 263-281.

Denham, N., Ackers, P. & Travers, C. 1997, “Doing yourself out of a job? How middle managers cope with empowerment”, Employee Relations, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 147-159.

Dopson, S. & Stewart, R. 1993, “ Information technology, organizational restructuring and the future of middle management”, New Technology, Work, and Employment, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 10-20.

Drew, J., McCallum, B. & Roggenhofer, S. 2004, Journey to Lean, Palgrave USA, New York

Fenton-O’Creevy, M. 2001, “Employee involvement and the middle manager: saboteur or scapegoat?”, Human Resource Management Journal, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 24-40.

Fine, D., Hansen, M. & Roggenhofer, S. 2008, “From lean to lasting: Making operational improvements stick”, The McKinsey quarterly, , no. 1, pp. 108-118.

Floyd, S. W. & Wooldridge, B. 1994, “Dinosaurs or dynamos? Recognizing middle management’s strategic role”, The Academy of Management Executive, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 47-57.

Harrington, D. & Williams, B. 2004, “Moving the quality effort forward – the emerging role of the middle manager” Managing Service Quality, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 297-306.

Hayes, A. 2008, “The Impact of Cuts to Middle Management on Control Environments-The Importance of Effective Monitoring of Controls; Brainstorming for Management Override”, The Journal of Government Financial Management, vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 60-62.

Holden, L. & Roberts, I. 2004, “The depowerment of European middle managers: Challenges and uncertainties” Journal of Managerial Psychology, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 269-287.

Huy, Q. 2001, “In Praise of Middle Managers”, Harvard Business Review, vol. 79, no. 8, pp. 72-79.

Huy, Q. 2002, “Emotional balancing of organizational continuity and radical change: The contribution of middle managers”, Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 31-69.

Jørgensen, F., Boer, H. & Frank Gertsen, 2003, “Jump-starting continuous improvement through self-assessment”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, vol. 23, no. 10, pp.1260-1278.

Keys, B. & Bell, R. 1982, “Four Faces of the Fully Functioning Middle Manager” California Management Review, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 59-76.

Lucey, J., Bateman, N. & Hines, P. 2005, “Why Major Lean Transitions have not been Sustained”, Management Services, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 9-13.

McCann, L., Morris, J. & Hassard, J. 2008, “Normalized Intensity: The New Labour Process of Middle Management” The Journal of Management Studies, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 343-371.

Moss Kanter, R. 1982, “The Middle Manager as Innovator”, Harvard Business Review, vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 95-106.

Mann, D. 2009, “The Missing Link: Lean Leadership”, Frontiers of Health Services Management, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 15-26.

O’Rourke, P. 2005, “A Multiple-case comparison of Lean six sigma deployment and implementation strategies”, ASQ World Conference on Quality and Improvement Proceedings, vol.59, pp. 581-591.

Psychogios, A., Wilkinson, A., & Szamosi, L. 2009, “Getting to the heart of the debate: TQM and middle manager autonomy”, Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 445-466.

Robyn, T. & Dunkerley, D. 1999, “Careering downwards? Middle managers’ experiences in the downsized organization” British Journal of Management, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 157-169.

Snee, R. 2010, “Lean Six Sigma – getting better all the time”, International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 9-29.